Information War: How PRS Students Learn about Ukraine v. Russia

We look at different ways global media portray the war and which types of media PRS students are getting information from.

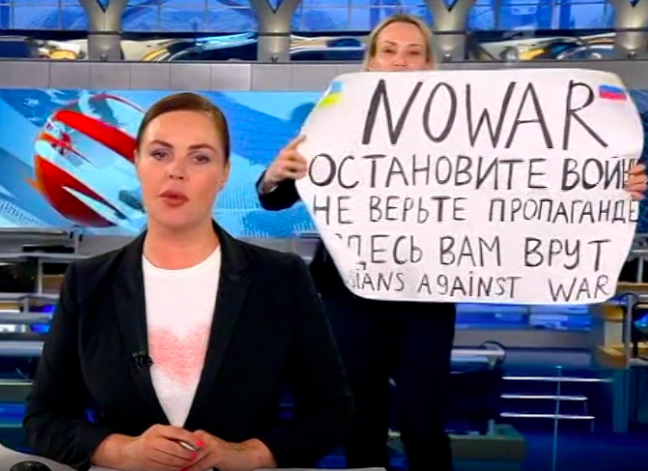

Marina Ovsyannikova protests the war in Ukraine on Russian TV news broadcast.

Ceaseless photos, videos and written words are being posted on Facebook, TikTok, Twitter and other media outlets, updating the world non-stop about the war in Ukraine. Newspapers, TV channels and radio stations are doing the same, including on their websites, presenting striking visuals of soldiers and military equipment in combat and the destructive impact on citizens and property.

Ukrainians and their supporters have used social media to deride the Russians, hoping to lift the spirits of Ukraine’s citizens and soldiers and lower the morale of the invaders during the most internet-accessible war in history. Russia has introduced new laws to shut down debate about the war, or even to stop people from calling the conflict a war, forcing many journalists and protesters into silence for fear of heavy punishments.

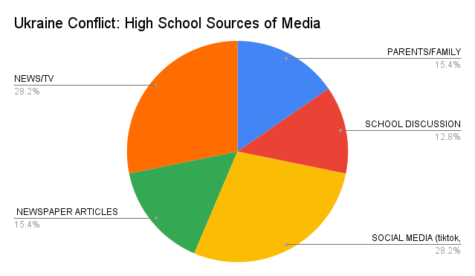

So where are PRS students getting their information about the war during this intense and non-stop information war? We interviewed 24 students for this article, sampling equally from Grades 7-12.

Middle school and high school students similarly reported that their main sources of information about the war in Ukraine are parents, electronic media (TV and radio), social media, news websites and school. Parents, electronic media and social media each provide about a quarter of the information students receive, with the remaining quarter divided evenly between news websites and school classes. Below are two pie charts showing the media sources used by the 24 students we interviewed.

In the middle school Grayson Pacelli (‘26) said, “I definitely listen to a lot of Ukrainian news, MSNBC, ABC, any of those kinds of news sources. Another one I use is the New York Times which is probably the most trustworthy and least biased.” Aleena Kim (‘26) said, “I’ve talked about it in American Studies. We talked about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and how it affected their citizens.” Miles Labovitch (‘27) said, “I’ve spoken to my family and my friends in SOCCOM class. We talked about it and we talked about whether America or other countries should go in and help.”

One SOCCOM (Social & Community Studies) teacher, Luke Michel, who is also the middle school principal, said, “I’ll ask them, ‘What sites do you want to look at?’ and they’ll say, ‘Fox News,’ and then something else, ‘New York Times,’ and then I’ll say, ‘Let’s go out of the United States,’ and I go to BBC. We are trying to make sure they look at a lot of different things. Like, who is putting what on the front page?”

In the high school too there was awareness about cross-checking different news sources. Tianne Chazin (‘22) said, “Social media coverage of the situation is a mixed bag,”and another comment was “I’m always hesitant to put my full trust in one source so that’s why I like to stay updated with multiple sources.” Aidan DeLange (‘23) said, “My main source is the news that me and my parents watch.” Laina Pond (‘23) said something similar: “My main news source is CNN articles and I watch the TV news, which is usually CNN, but also Fox sometimes to see what their view is too.” Ben Vu (‘24) commented, “My main source is my dad, social media and friends” and Soren Schilling (‘23) said, “friends and Instagram.”

Valentina Huynh (‘22) had a lot to say on this topic. “We talked about it in AP US History class, so mainly here in class and on the news, just CBC, CNN. I actually do follow the news from Vietnamese media as well. There is one outlet called Young People’s News and it’s just… it’s pretty opinionated, but I like to read it just to see different points of view. I trust the US media, like the New York Times and CNN because they have a good reputation, but overall you can’t rule out the fact that media are biased, so I take it with a grain of salt I guess.”

In Journalism & Media Studies class we looked at coverage of the war in Ukraine on websites for newspapers, TV stations and other media from around the world, including media from every continent and many countries and languages. We also looked at social media phone apps like Instagram, WeChat, Telegram, TikTok and Twitter. On American social media the majority of postings supported Ukraine, but on social media based in China views were generally more neutral or supported Russia, while on Telegram there was a mixture of Russian, Ukrainian and neutral messages.

We noticed the same patterns of political differences based on national and linguistic differences in both social media and legacy media platforms. So that suggests that national laws and politics, combined with language differences, create filters on information and explanations about the war. As Charles Fenner (‘26) said when we visited the middle school, “There are some numbers that seem a little weird, like apparently Ukraine claimed they killed over 4,000 Russian soldiers, but also Russia has claimed that zero of their soldiers have died.”

A dramatic example of how the media is itself part of the power struggle in the war was seen when Marina Ovsyannikova, an editor at Russian news station Channel One, sneaked onto a live TV news broadcast and held up a sign protesting the war in Ukraine. The sign in Russian read: “Stop the war. Don’t believe the propaganda. They’re lying to you.” Beforehand, Ovsyannikova recorded a video in which she explained the reasoning behind her action, how she felt ashamed for having helped spread Kremlin propaganda. After her surprise protest she was arrested and kept in custody by the Russian police, but eventually she was able to leave Russia for Germany, although without her children.

The power struggle for control of Ukraine war information shows how the media have evolved from a propaganda battleground to a tool for real-world invasion and resistance. In the so-called Information Age of the 21st Century the new types of media technology now guarantee that the information war is always a huge part of the actual war in real time, 24/7. That means, in a way, that PRS students and everyone else is on the battlefield now too, as the media bring the war to everyone 24/7 and not just in classroom discussions or conversations with peers or parents.

For more of our coverage of the war in Ukraine, see “War in Ukraine: Why is it Happening?” by clicking here, and “War in Ukraine: PRS Students React” by clicking here.

Annita Geng is a senior at Pacific Ridge School and plans to attend Boston University next year, where she intends to major in business and minor in literature...

Ashay Kalthia is an enthusiastic junior at Pacific Ridge School. This year he discovered his new passion for journalism and he loves to write stories about...

Cassiella Brown, a junior, is in her first year of Journalism & Media Studies at Pacific Ridge School. She enjoys writing stories about sports, community...

Erick Maganda Santiago is a junior at Pacific Ridge School and he is interested in photography, reading and languages. For The Egg he is a writer and photographer...

Hannah Tison is a junior at Pacific Ridge School who loves to cover events and trends impacting students on campus. Her passion for community-focused...

Reese Walsh is a junior at Pacific Ridge School, where she plays on both the indoor and beach volleyball teams (along with club beach volleyball). She...

Vivian Zhang is a senior at Pacific Ridge School and a rising freshman at UC Berkeley. As an aspiring Media Studies major, she finds entertainment and...