On September 11th, 2001, the terrorist group Al-Qaeda carried out a series of attacks on the United States. From 7:59 to 8:42 AM, Al-Qaeda hijacked four commercial planes, crashing two into the World Trade Center, one into the Pentagon and one into an empty field in Pennsylvania. The planes included American Airlines Flight 11 and United Airlines Flight 175, both of which took off from Boston, American Airlines Flight 77 which took off from Dulles, Virginia, and United Airlines Flight 93 which took off from Newark, New Jersey. All flights were bound for California.

At 8:46 AM, Flight 11 crashed into the World Trade Center’s North Tower, leaving an extensive hole in the building near the 80th floor. Just 18 minutes later, Flight 175 was broadcast live on news stations as it struck the South Tower around the 60th floor. 200 miles south, 34 minutes later, Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon in Washington DC. Just over two hours after the initial hijacking, Flight 93 crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers fought with the hijackers for control of the plane.

On the four planes combined, there were 213 passengers, 33 crew members and 19 hijackers, all of whom were killed. The official death toll of 9/11 is set at 2,977 people on the day, including those in the buildings that were struck, with hundreds of thousands more affected. The rubble, debris and dust from the impact contained hazardous substances, including asbestos which is a toxic mineral that is known to cause lung disease if inhaled. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 400,000 people may have been exposed, with hundreds more dying later from results of that exposure, including many first responders.

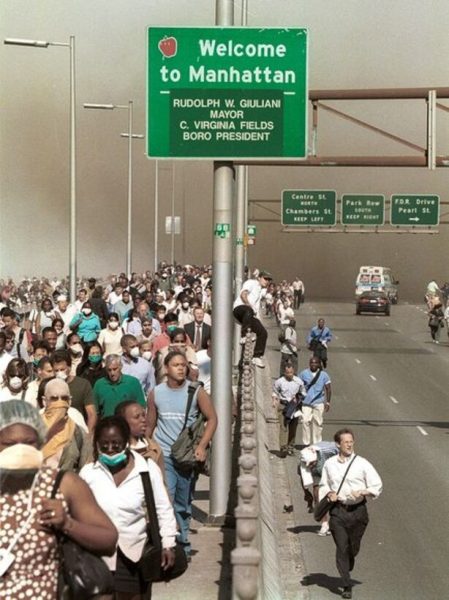

As smoke blanketed the sky, a wave of confusion fell over New York City. Pedestrians stared in disbelief at the burning buildings, unsure about the safety and future of our nation. Even greater shock was felt when each tower of the World Trade Center collapsed while there were still thousands of people inside them, including many first responders who were trying to rescue the occupants. In the days that followed, emotions flooded through the city, the country and around the world.

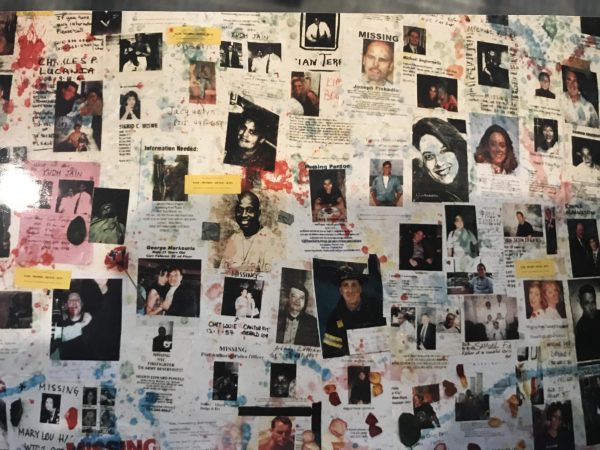

Throughout New York City, grief manifested physically in the candles and pictures dedicated to missing loved ones. Mr. Aaron Gillego, a PRS English teacher who lived in NYC during 9/11, shared that “all the arteries into the city were closed, the buses, the tunnels, the subways, the bridges.” As the city shut down, civilians tried to make sense of the disaster. Pacific Ridge parent and New Yorker at the time, Kate Nazif, recounted her experience. “[New York] is a hard city, it’s fast-paced, and there was a sudden shock to the system as everything slowed down.”

While the city slowed down, the military kicked into action. Dr. Thieken, PRS math teacher and former E5 sergeant in the U.S. Army recalls his experience during 9/11 in Washington DC where the Pentagon was hit. Dr. Thieken was an army E4 specialist at the time and his job was to stay at the Pentagon as the fires were brought under control. “For the first two days, the Pentagon was still burning so nobody went in except the firefighters. We would sit there and just watch it burn.” He shared a haunting memory from the time: “It was 3 AM… I saw the Pentagon where everything was built up and still all burnt out, and there was just a firefighter playing with his rescue dog.”

Hugh O’Donnell, former PRS parent and current PRS hockey team president, has an extensive national security, public safety and criminal justice background. He served in the United States Marine Corps from 1971 to 1994, rising from 2nd lieutenant to lieutenant colonel. At the time of 9/11, Mr. O’Donnell worked for the Oracle Corporation, where he led a project team supporting criminal justice information projects for the state of California. On the morning of September 11, Mr. O’Donnell was on a plane in San Diego awaiting departure for Sacramento when the plane was ordered to return to the terminal. Soon after 9/11, Mr. O’Donnell attended the International Association of Chiefs of Police meeting in Toronto and shared how “there was a sense of shock that everybody felt about what had happened.” The meeting was focused on “trying to understand who the real enemy is and how we need to deal with the enemy.” 9/11 was different from prior conflicts, as there was not a clearly identifiable enemy to fight.

Following the attacks, the U.S. president at the time, George W. Bush, announced his “Global War on Terror” on September 16th, 2001. This was a comprehensive plan from the government to seek out and stop terrorists and “rid the world of the evil-doers.” Following the Taliban’s refusal to hand over Osama bin Laden, the leader of Al-Qaeda, the United States launched airstrikes and deployed ground forces against Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan in partnership with NATO allies. U.S. involvement in the Afghanistan conflict would not end for another 20 years. Spencer Burrows, PRS U.S. Government and Politics teacher, explained how 9/11 was a turning point that led to “the War on Terror, sending troops into Afghanistan, and then the invasion of Iraq.”

In October 2001, the Patriot Act was passed through Congress, expanding the government’s surveillance abilities and the scope of law enforcement’s authority. In November, the Transportation Security Act (TSA), was established and signed into law. Two years later, in March 2003, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was established by President Bush to coordinate efforts to protect the U.S. from terrorism.

As new laws regarding privacy versus security were introduced, many civilians grew increasingly concerned about their civil liberties and First Amendment rights. Martha King, a Pacific Ridge parent, remarks “The police state has gotten worse, privacy has gotten worse, and the police have been militarized.” Others argue that these laws are needed for protection. Former U.S. Senator Joseph I. Lieberman commented that “building this Department will involve no shortage of problems, as any massive undertaking of this kind would – but we, after this initial act of creation, must be ready to improve, to support, and ultimately to protect the American people,” emphasizing that, “we have no choice.” This ongoing debate continues to be at the forefront of politics today.

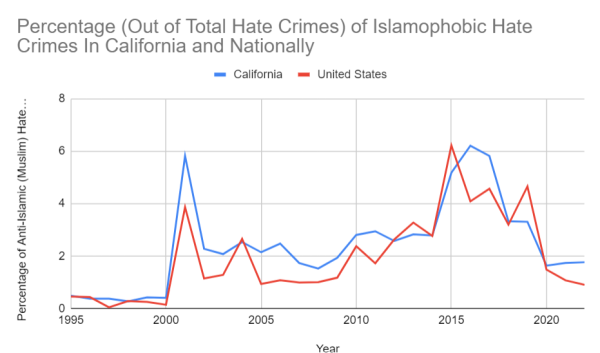

Islamophobic hate crimes escalated in the U.S. after the 9/11 attacks. According to FBI statistics, between 1995 and 2000 Islamophobic hate crimes averaged 0.39% of total U.S. hate crimes before spiking to 5.82% in 2001. According to Tom Smith, director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Society at the University of Chicago, statistics from the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service indicate that Muslim Americans made up less than 1% of the population circa 2001. Comparing the percentages, there is a disproportion between the two, indicating a widespread rise in hostility towards Muslims in the U.S. after 9/11.

At the same time, there was an increase in the visibility of polarizing interpretations of Islam in the public sphere. One of these interpretations is Wahhabism, the branch of Islam Al Qaeda follows. Jamsheed K. Choksy, distinguished Professor and current Director of the Inner Asian and Uralic National Resource Center at Indiana University, and Carol E. B. Choksy, adjunct professor at the School of Library and Information Science at Indiana University, have written that “Wahhabism in turn emerged as the “indispensable ideology” – as noted in the record of the US Senate Subcommittee on Terrorism, Technology and Homeland Security – not just for the Saudi state but also for groups such as al-Qaeda, which took up the mission to enforce a purified form of Islam upon the world.” According to Paul Marshall, Senior Fellow of the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom, the particular ideology that is taught includes that “you must not have any good contacts, warm relations with anybody – not only with unbelievers, but with any Muslim who is not of the Wahhabi type.” These extreme beliefs have been used as a justification for violence.

Janet Nazif, PRS grandparent, worked for over 25 years as a teacher, head of school and administrator at Noor-Ul-Iman, an Islamic school in New Jersey. She shared that there was a palpable sense of “fear in the Muslim community” after 9/11 as hateful messages spread across the United States. To combat this, the school turned to community outreach, because “if we [Muslims] didn’t want to be known as terrorists, we had to teach people about our religion.” The school opened for people to visit and experience its joyful community while Islam was taught alongside subjects such as Math and English.

Beyond the political ramifications of 9/11, many people were emotionally affected. According to the New York Magazine as of 2014, 20 percent of Americans knew someone hurt or killed in the attacks. Mr. Burrows shared his heartbreaking memory that “everybody knew somebody who died in the crash or died soon after.” Several other Pacific Ridge community members shared similar perspectives.

Weeks after 9/11, many citizens felt uneasy looking toward the future of the United States. Kate Nazif shared that “anytime an airplane would fly over the city, people would stop and just look up.” Citizens were on high alert wondering whether something horrifically similar would happen again. Ms. Grossman, PRS Assistant Head of Upper School, has a daughter who was ten months old at the time. Ms. Grossman shared that she remembers feeling “super scared for what kind of world [her daughter] was going to grow up in.” 9/11 left citizens in a state of shock and concern, a feeling that hasn’t dissipated.

In the years since 9/11, the United States has repeatedly come together to remember the lives lost. But at Pacific Ridge are we doing enough? When asked this question, Ms. Grossman said that she believes “we have an obligation to talk about it.” Perhaps through more assemblies, class lessons, and activities to promote awareness, PRS can be sure that students understand the magnitude of this tragedy. Mr. Gillego reminds us that since high schoolers today were born after 9/11, “they need to always be taught about that history.”

The diverse perspectives of PRS teachers highlight the necessary balance between imparting historical knowledge and respecting individual experiences. “It’s okay that kids here have never heard about 9/11,” Dr. Thieken believes, “that’s my history, not theirs.” Ms. Lyman, PRS physics teacher, added that “a lived experience will never be the same as a learned experience” and “I don’t think there’s the opportunity in the way our school system is designed to give enough time to really unravel all the implications.” The debate on how to teach this tragedy reflects the complexity of conveying a shared history to a generation born after these events. As we navigate these discussions, it is clear that the legacy of 9/11 is not just a crucial historical marker, but a tragic memory for many.

As our nation faces new challenges in the current age of media, Mr. O’Donnell provides pertinent advice to the current generation of PRS students: “Take your skills, take your talents, make a difference. Take on the tough challenges. Don’t be ordinary.” While the legacy of 9/11 continues to impact our nation, we must simultaneously focus on tackling current global issues. In a community that focuses on “ethical responsibility and global engagement”, it is our responsibility to understand the world around us, and take on pressing challenges.